Can We Fix Puget Sound’s Beaches?

by Christopher Dunagan

Part 1

New numbers show progress in the state’s efforts to remove shoreline armoring, but they don’t tell the whole story.

For the second year in a row, more shoreline armoring — such as rock and concrete bulkheads — has been removed than constructed in Puget Sound, according to permit statistics compiled by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

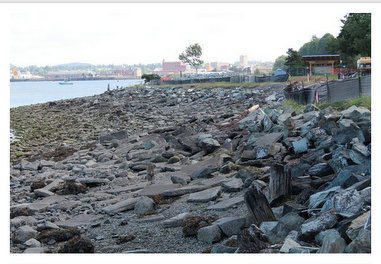

Before photo: The Boulevard Park shoreline was eroding away as a result of ineffective shoreline armoring. photo: Reddit

In 2015, 3,097 feet of old armoring were removed from Puget Sound, compared to 2,231 feet of new construction.

Shoreline experts have cautiously embraced the news, which comes amid new studies describing the ecological damage caused by bulkheads. Meanwhile, state and federal agencies have increased programs to assist property owners in removing unneeded structures or else replacing them with more natural erosion controls.

“We have put forth a whole lot of effort, and we have seen the needle move in the right direction,” said Dave Price, restoration division manager for WDFW. “There is hope for the future, but there is still a lot of work to be done.”

After photo: Improvements included creating sand and gravel beaches and rock revetments. photo: Reddit

Price and his team have translated the challenge into a statistic as concrete in the bulkheads that line Puget Sound. Price’s optimism is tempered, he says, because more than 700 miles of shoreline armoring still remain.

That number is greater than the length of the ocean beaches in Washington and Oregon combined, and it covers more than 25 percent of Puget Sound’s winding shoreline, a collective “great wall” built by property owners to hold back erosion.

Even though the state now measures progress for armor removal in mere feet, the recent figures still mark a turning point. From 2005 to 2010, the addition of new bulkheads averaged more than a mile a year across Puget Sound, and removal was hardly a consideration. In earlier years, new walls were being built along the shoreline at an even faster pace.

Last year, new bulkhead construction totaled 0.42 mile, actually up from the all-time low of 0.29 mile the year before. But a larger amount of removal — 0.58 miles in 2015 compared to 0.45 mile in 2014 — made up the difference, continuing the net decline for two years straight.

New Priorities

It is well understood that the benefits of removing an old bulkhead may or may not counterbalance the damage caused by building a new bulkhead of the same size. It is all a matter of location.

Restoration programs are placing the highest priority for removal on spawning areas used by forage fish, such as surf smelt and sand lance. Also high on the priority list are shorelines that supply sands and gravels for healthy beaches. These shorelines are sometimes called “feeder bluffs.” Landowners may qualify for grants to remove or replace their bulkheads, especially where the environmental benefits are clear.

Megan Dethier, a research biologist at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories, led an extensive study of armored and natural shorelines in Puget Sound. The study found that beaches containing bulkheads were generally narrower and contained less shoreline vegetation and driftwood, leading to lower species diversity and less food for juvenile salmon, marine birds and larger animals.

Dethier’s study, published in April 2016, is the first to describe the cumulative effects of bulkheads along stretches of shoreline in Puget Sound. Heavily armored areas tended to have less sand and more accumulation of coarse sediment and rocks, especially where bulkheads blocked natural erosion.

“Some shorelines are armored right in front of bluffs that have no houses or the houses are set way back,” said Dave Price, restoration division manager for WDFW. “I see that all over the place. A little sediment coming off these hillsides can be a very good thing for fish, and I don’t think they are a problem for landowners.”

A major effort is now underway to help shoreline property owners understand these effects, Price said. Many people acquired outmoded bulkheads when they bought their property and are not aware of the long-term effects.

“I was on the water a couple days ago,” he said during an interview in August. “It is pretty remarkable how many bulkheads were built from the 1950s to the ‘90s just to accommodate picnic areas that seem totally unnecessary.”

At the same time, more and more people are using “soft-shore” techniques to reduce erosion where waves and currents threaten to damage their homes. Ideas include sloping a beach and anchoring logs or large rocks on the beach to absorb the wave energy. Such projects are considered less damaging to the ecosystem than hard bulkheads.

Understanding the Natural Process

Cities and counties that have updated their shoreline regulations the past few years no longer allow hard bulkheads unless a significant structure, such as a house or a road, is at risk of damage within three years. These standards are derived from the Washington Department of Ecology, which plays an equal role in developing local shoreline plans.

2018 Shoreline Armoring Implementation Strategy Finalized

Following a public comment and external review period, the Habitat Strategic Initiative team released the Shoreline Armoring Implementation Strategy, which aims to reduce shoreline armoring in Puget Sound. For more information, please visit https://pugetsoundestuary.wa.gov/2018/04/25/shoreline-armoring-implementation-strategy-finalized/.

Property owners often can save themselves the cost of building and maintaining a shoreline structure if they understand the annual erosion rate of their property, said Hugh Shipman, a coastal geologist with Ecology.

“[Erosion] rates are very slow on Puget Sound, and many properties would do just fine without bulkheads,” he said. “Sometimes this requires recalibrating our personal desire to control small rates of erosion or our fear of scenarios that aren’t realistic.

“Having said that, there are places where erosion needs to be considered very carefully — most commonly on some high bluffs, on landslides, and where the at-risk structure is really close to the edge.”

If building a new bulkhead has undesirable effects on the Puget Sound ecosystem, then removing old bulkheads should help with the recovery effort, experts say. As part of a four-year focus on shoreline issues, the Environmental Protection Agency funded seven major beach-restoration projects involving the removal of bulkheads.

But it’s not easy. And it’s not cheap. In all, those projects cost about $8 million between 2012 and 2016 to remove just under a mile of shoreline armoring. Such restoration projects go beyond just armor removal and are critical to Puget Sound recovery, agencies say, but they won’t solve the problem on their own.

Of those seven projects, the type and amount of habitat improved with the bulkhead removal varied from project to project. By measuring habitat conditions before and after the work was done, researchers hope to describe the benefits of each project.

First published by Encyclopedia of Puget Sound: https://www.eopugetsound.org/magazine/fix-beaches.

Next Month: Part 2

___________________________________

Christopher Dunagan is a senior writer at the Puget Sound Institute, which is affiliated with the University of Washington.