The Nooksack River The History and Current State of the River

The River with boulders and logs washed down with Spring floods, looking North. Photo: Ron Kleinknecht

by Ron Kleinknecht

Part 2

In part 1 of this series, I described the Nooksack River from its headwaters and contributing forks in the North Cascade Mountains through its course to the Salish Sea. (1) I made the case that this river, along with others like it, was critically important to sustaining our icons of the Salish Sea — salmon and orcas. Sustaining these icons is dependent in part on the health of these rivers that nourish the fish, which in turn feed our resident orcas. A focus needs to be on restoring and maintaining lush and unpolluted ecosystems, which in turn make for healthy rivers and healthy fish. In this part I relate the history of the river, what has happened to it, and why it is important today that it is restored to health and maintained.

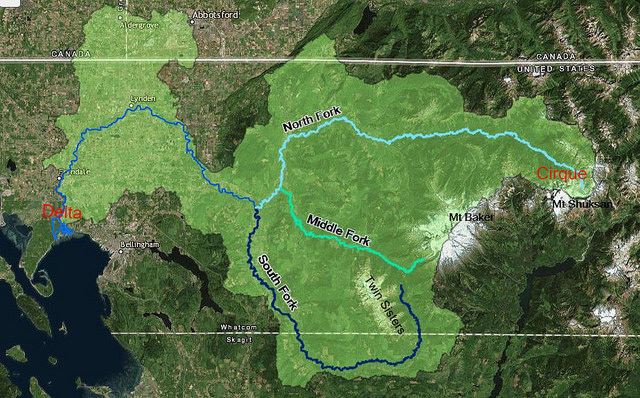

Three forks and the main stream of the Nooksack River. North fork begins at Nooksack Cirque at far right and meets Bellingham Bay at the river delta at the far left. Light green covers the river drainage, some of which reaches into British Columbia. http://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=6119202fe2f8434db4c43c4d8920d209

On casual viewing, most of this river appears robust and healthy as seen in Part 1. Although much of the river is in pretty good shape, closer examination shows that it is not totally pristine, especially as it pertains to our aquatic friends. In general, the river is relatively healthy in its upper reaches and deteriorates progressively as it flows toward the sea (which corresponds with the increased density of residential and agricultural occupation). The story of the Nooksack River has been written numerous times of other rivers all across the continent from east to west. The Nooksack was one of the last to experience change, as the area was not settled until the mid to latter part of the 19th century.

For a time perspective on the decreasing return of salmon in the Nooksack, we should consider an interaction that I had recently with a conservationist from Maine. The conservation group that he worked with had recently seen Atlantic salmon return after years of river restoration. Prior to this return, it had been 300 years since salmon had last swum in that river.

As noted, the Nooksack and Lummi Indians have flourished in this area along the river for thousands of years, as it provided them with an abundance of everything they wanted and needed. The river teemed with salmonids much of the year, including each of our five Pacific salmon species as well as steelhead and trout. They had nutritiousnroots of all kinds, including their namesake the “Nooksack” — bracken fern roots. (2,3) In addition to salmon and roots, they had access to all the meat they could process, including deer, elk, bear, beaver, mountain goats, cougar, birds, shellfish and more. They had dense forests of Douglas fir and western red cedar that provided lumber for their longhouses and canoes. For thousands of years they had lived as part of this natural system. They wanted for little.

Arrival of White Settlers

Then, in the latter 1850s and thereafter, white settlers showed up and staked out homesteads along the river and in its watershed. (3,4) Although they seemed to have gotten along well with local Indians and many became lifelong friends, the new settlers brought their ways that began changing the character of the land and therefore the river. The new homesteaders saw these natural wonders as something to be used to their advantage, and they were good at exploiting them.

From the time of the settler’s arrival in the Puget Sound region to the present, about 160 years, between 50 and 90 percent of the land along its streams and rivers has been lost or extensively modified. (5)

The first homesteading took place in the flat prairie land surrounding the lower 30 miles downstream from where the south fork joined the main river. These flat lands were covered with timber and large expanses of ferns, hence one of the early towns was named “Ferndale.” (3)

The first thing the new settlers did was clear the forest and fern prairiesn for farmland. Since the river was their main mode of transportation, they first cleared and built along its banks. Because they wanted boats larger than dugout canoes to bring equipment and supplies up the river, they cleared out an enormous natural log jam just south of Ferndale that ran nearly a mile. Removal of this log jam allowed them to get a steamboat upriver to Ferndale and to Lynden. (3) This modification of the river might have been the first significant blow to the Nooksack’s salmon spawning territory.

The logs from the prairies and hills were skidded to saw mills which were situated by the river. The mills and logs further stirred up the stream, destroying spawning grounds. This logging and farming denuded much of the river’s lower watershed, leaving bare land without natural flora to capture the rain and the flooding runoff. And it continues yet today, although it is being better regulated.

This first settled part of the river regularly flooded the crops. It is now mostly diked and dredged, further impairing the salmon habitat in the first 30 or so miles. The fish must swim at least 30 to 50 miles to reach the forks and feeder creeks to find adequate spawning beds. Human population growth continues with more farms, vacation housing developments and logged hillsides. Local, state and national efforts continue to evolve with increasing environmental regulation and government and NGO programs to preserve the remaining waters. (6)

Nooksack River Unstable

A recent appraisal of the state of the river by a local district biologist for the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife, Brett Barkdull, described the river as unstable. (7) Dramatic changes in water flow from rain-caused floods either washes away redds (nests) or smothers them with mud. Alternatively, the summer low waters leave them to dry out.

“Our biggest problem is egg-to-fry survival,” Barkdull said. “There’s basically no habitat left in the main stem … The Nooksack has been diked, ditched, straightened. Any evil you can commit on a river has been done to the Nooksack.” (7)

That pretty well sums up the state of the lower reaches of the Nooksack River, and, as noted above, progressively less so moving upstream. As a whole, the river is still viable and salmon do pass through these lower reaches to find spawning grounds upriver. But there are big problems, the greatest of which is the loss of salmon habitat and therefore spawning salmon.

Wild salmonids (except sockeye) in most of the streams feeding the Salish Sea are listed as threatened, according the Endangered Species Act. (5) (Chinook, steelhead and bull trout are listed as endangered.) Their numbers have plummeted in recent years, and are nearly gone in many streams that flow into the Puget Sound. Although all five species still find their way home and spawn in the Nooksack River or its tributaries, the numbers are small, as is the case for most all streams leading into the Salish Sea. Recent reports show that since the 1970s, the three species shown above have experienced a tenfold decline during the time they spend in the Salish Sea. (8) https://www.eopugetsound.org/magazine/marine-survival-project

River, Salmon and the Ecosystem

Most salmon spend much of their first year or so in freshwater streams, and this first year is critical to their ultimate survival. To the extent that their stream is healthy and supplies adequate food, the fry can grow larger and faster, traits that decrease their chances of being eaten by larger prey. After leaving the river and estuary, even more are lost while at sea. The early rearing conditions are critical to their ultimate survival and return, the rate of which is diminishing significantly. Over the past 50 years, Salish Sea salmon and steelhead survival rates (returning to spawn) have shrunk from 3 per 100 to just 1 per 100. With that rate of loss, these fish are clearly not sustainable for long.

One factor affecting stream health that has received considerable study recently is stormwater runoff from roads, streets and parking lots. These waters contain numerous toxic chemicals including heavy metals and hydrocarbons, all of which are highly toxic to fish. (8) When those returning salmon — that survived the river, the estuary and the ocean — arrive as adults to spawn, many are exposed to concentrations of these chemicals. Of those so exposed, many develop what is now called the “urban runoff mortality syndrome.” (8) In the past decade, up to 90 percent of coho salmon in urban streams in the Puget Sound watershed died before they could spawn because of toxic stormwater runoff. (5)

The video here tells the story of our urban runoff including a Coho dying from “urban runoff mortality syndrome”: https://youtu.be/1JDsFJJJHSY.

We often hear the catchphrase: “save the salmon” — which is a worthy goal. However, more accurately, we should say: “save the river and its ecosystem” and then the salmon can be saved. These fish do not exist in isolation as they are part of a highly interdependent network of both flora and fauna, all parts of which must be preserved and brought back into a natural balance.

A creek or river’s biological health is indexed by the number and types of stream denizens which feed the salmon, such as benthic macroinvertebrates. (9) These small, spineless animals, including insect larva, vary in their tolerance to pollution. Some, such as caddisfly and mayfly larva, are intolerant to pollutants and will not be found in an unhealthy stream. Others, such as dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, amphids, freshwater clams and mussels, can tolerate some pollution. Other critters, such snails, leeches and aquatic earthworms, are less affected by polluted waters. If you find only these latter creatures and none of the larva or nymphs, there is good chance that the stream is unhealthy for salmon and for other fish.

These benthic invertebrates are important food sources for young salmon fry, as they mature after hatching in spawning streams. Other stream critters, including birds such as the American dipper, also eat dragonflies, various larva, worms, small fish and salmon roe.

Keystone Species

Not only do these invertebrates nourish salmon, salmon also contribute nourishment to them and other critters. Salmon are referred to as a “keystone species” in both aquatic and terrestrial environments, in that nutrients from their decaying bodies after spawning contribute to the survival and reproduction of some 137 different species. (10) These species include the salmon themselves, trout, eagles, ravens, crows, bear, wolves, coyotes, river otter, and other mammals who feast on their eggs, carcasses, or their young. And it is not just other animals that salmon nourish.

A recently spawned salmon goes down the eagle hatch near the confluences of North and Middle Forks. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

Also very important to the riparian environment along the streams is that the decomposed salmon carcasses provide nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus for algae in the streams, as well as for trees and shrubs along the stream. An interesting correlation has been found between the size of a given year’s salmon run and the nitrogen levels found in tree growth rings along a river’s riparian zone. (11,12) This occurs when the above animals carry salmon from the river to the adjacent woods, where they devour the most nutritious portions of the fish, eating mostly their bellies and roe. They then leave the rest of the carcass with its nutrients to decompose into the soil. (13)

Salmon feed the whole gamut of wildlife that lives in or near their streams, and thus are important for sustaining their own ecosystem. Without salmon we will be left with barren, sterile, stinky and muddy water running to the sea, which in turn will be barren and lifeless. Without healthy streams we won’t have all the healthy forest and stream creatures that depend on them.

The river’s pollution does not end when it reaches the salt water. It flows into the intertidal shores and continues its adverse affects. Pollutants such as excessive nitrogen and phosphorous from farm manure and fertilizer seepage and runoff fosters rapid phytoplankton growth, especially in warmer temperatures. (Note, some of these nutrients are necessary, but too much is harmful.)

Often, but not always, these “blooms” of algae turn the water red, and are commonly referred to as red tides. Since they do not always turn the water red, they are more accurately called “harmful algae blooms” (HABs). (14) Bivalves (clams, oysters, mussels) consume and even thrive on these algae without harm. However, certain algae accumulate in the shellfish, building to levels that are toxic and even fatal to humans, marine mammals and even salmon. (15) When the HAB levels become toxic enough to cause Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning, the Whatcom County Health Department closes all shellfish harvesting (recreational and commercial) to protect the public.

The pollution that fouls the river water affecting the macroinvertibrates and fish moves on to taint the estuaries and tidewaters (shellfish). From there, the polluted water flows into the salt water affecting all marine life there, including fish and whales of the Salish Sea.

The animals most dependent on the salmon for their lives are the resident orcas that have lived in the Salish Sea for eons. Our three local resident pods, designated J, K, and L, rely solely on a salmon diet or they starve. Like their food source, salmon, the Salish Sea resident orcas are in serious decline. What happens upstream in the Nooksack (and other rivers) does not just stay in the stream. It flows to the sea.

Critical Juncture

In a nutshell, the salmon habitat has been degraded. The salmon have been overfished and their waters have been polluted and poisoned. At issue is the health of the entire ecosystem including the river, its shores and its watershed. Following is an enumeration of some of specific factors contributing to the decline of this river. Clearly these are not unique to the Nooksack River.

Clearing log jams, beaver dams and debris that naturally accumulate to create deep pools and slow-moving waters have destroyed or reduced spawning beds in the lower stretches of the river and cool water for fish to grow and mature.

Artificially banked levees for the last 30 miles were constructed to protect farmlands from flooding, but preclude natural stream hydraulic processes.

Spawning beds have been fouled by mud flows, floods and slides from surrounding logged and developed hillsides.

Tributary creeks which are also spawning creeks have been crossed by roads built over with culverts that replace the natural streams, straining or preventing salmon to navigate to their spawning areas.

A diversion dam on the Middle Fork directs river water to Lake Whatcom to supplement Bellingham’s drinking water supply. It has blocked salmonids from returning to their historic spawning grounds since 1962. (16)

Agricultural product runoff and seepage, such as animal manure and chemicals used as fertilizers, contaminate the river and streams. Similarly, septic tank leakage is another problem in some the rural districts.

Wells drilled into aquifers sap water from streams during low-water periods, leaving fish high and dry.

Stretches of the river are warmed due to loss of riparian zone trees and shrubs that shade the streams. Warmer stream water is likely to increase as we experience increasing climate change in the future. Salmon need cool and well-oxygenated waters to thrive.

Trash, including plastics and other toxic materials, continues to be dumped at many points along the river, and residues from roads, parking lots and other paved surfaces drain into the river.

There you have it, a brief description of the Nooksack River with some of its current ills and its history from being a cornucopia to the Nooksack and Lummi Indians and their related tribes for thousands of years. In just the past 150 years, it has been nearly brought to its knees through use and abuse.

The next two parts of this series will describe some of the many, often heroic efforts, underway to address the above enumerated problems and to reclaim and restore the river and its ecosystem. Many agencies are actively involved in this restoration project that includes: our cities, Whatcom County, state and federal governmental agencies, the Nooksack and Lummi tribes, along with several NGOs and their hundreds of volunteers.

Next Month: Part 3

What Can Be Done to Rehabilitate the Nooksack?

References

1. Whatcom Watch, March, 2019.

2. Richardson, A, and Galloway, B. (2012). “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture and Language,” UBC Press, Vancouver, BC.

3. Jeffcott, P.R. (1949), “Nooksack Tales and Trails.” Ferndale, WA.

4. R.E. Hawley (1945), “Skqee Mus; Or, Pioneer Days on the Nooksack,” Miller & Sutherlen Pub., Bellingham, WA.

5. https://stateofsalmon.wa.gov/exec-summary/

6. https://ecology.wa.gov/Water-Shorelines/Water-supply/Streamflow-restoration

7. https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article171852652.html

8. https://fws.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=5dd4a36a2a5148a28376a0b81726a9a4

9. https://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/indicators-benthic-macroinvertebrates

10. http://pebblescience.org/salmon_ecology.html

11. http://web.uvic.ca/~reimlab/salmonforest.html

12. http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=407.

13. https://www.nature.com/news/2001/011001/full/news011004-4.html

14.https://www.doh.wa.gov/CommunityandEnvironment/Shellfish/RecreationalShellfish/Illnesses/Biotoxins

15. https://www.eopugetsound.org/magazine/ssec2018/marine-survival-4

16. https://www.cob.org/services/environment/restoration/middlefork/Pages/middle-fork-background.aspx

________________________________

Ron Kleinknecht is professor emeritus of psychology and dean emeritus of Western Washington University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He’s a lifelong nature and conservation enthusiast who writes about the Pacific Northwest and is a volunteer land steward for the Whatcom Land Trust.