How Is Whatcom Dealing With Recyclables?

by Nichole Schmitt

In 2018, the United States became suddenly aware of how ill-equipped we are for handling our own waste. Without much advance notice, China stopped accepting the world’s garbage. Shipping containers were turned away at the port and told to take their trash back home. China still takes certain high-quality recyclable plastics, but most U.S. waste facilities do not have the ability to sort plastic waste to that level of granularity.

Like a home with a malfunctioning septic tank, we could no longer flush. Some U.S. cities stopped picking up recyclables and told citizens to simply put it all in the trash. Other cities continued to collect recyclables, but sent it to landfills or incinerators. These incinerators were designed only to burn trash, but now they burn plastics, sending carcinogenic air into surrounding neighborhoods. This is unconscionable. But what else is to be done?

How is Whatcom County faring in this situation? Compared to other cities and states, we are lucky have a well-functioning disposal network. Well-functioning, that is, according to today’s standards. A large portion of thanks should go to Northwest Recycling, Inc. According to their discreetly tucked “About Us” page, the Parberry family has been dealing with our junk for almost 100 years. Marty Kuljis, NWR operations manager, kindly gave my family a tour and explained how Whatcom’s recycling is collected and processed.

Comes Down to Recipes

Our education began as we handed Marty a bundle of plastic bags and he removed a few of the bags that are not recyclable. Why? Without going into a chemistry discussion, it comes down to recipes. To make a new plastic widget from reclaimed plastic means you must gather only certain types of plastic ingredients for your recipe. Acceptable ingredients include clean and dry plastic shopping bags, sandwich bags, produce bags, and the plastic shrink wrap that surrounds your cases of bottled water. But Marty pulled out all my plastic cling wrap and the frozen-food bags and vetoed them over to the trash. Frozen-food bags often contain nylon or vinyl. This makes the bags stronger, allowing them to survive the life they were designed for, but not allowing them to be recycled. NW Recycling offers a drop-off bin for your clean and dry plastic bags, but a more convenient drop-off location for you might be Haggen or Safeway.

Next stop — paper — and more about recipes. Factories that purchase our waste paper require specific mixtures and ratios of cardboard, newsprint, and mixed paper. They turn these ingredients into things like corrugated cardboard and egg-carton-style cushions for peaches and apples. The Whatcom County public should think of themselves as suppliers of ingredients for “customers” who are willing to recycle our waste. To retain the customers, we should provide a high-quality product. In other words, as we plop our paper and cardboard at the curb, let’s not add greasy pizza boxes. Compost them instead! Green Earth Technology, LLC, takes all of Whatcom County’s compostables. Most of the donors who bring waste to the Lynden site are commercial-sized enterprises. But household waste can be brought directly to them as well. Items include yard waste, kitchen scraps, and bio-degradable containers. Sadly, our wax-coated cardboard containers, such as milk or ice-cream cartons are not acceptable for composting because the wax often contains plastic. Furthermore, many are lined with foil — also not compostable!

Aluminum

Speaking of foil — let’s talk about aluminum. NW Recycling currently ships our cans to a factory in Alabama where they are converted into new cans and are back on store shelves within six weeks of leaving Whatcom County. If you personally deliver your cans to NW Recycling, you can get a little cash for them. If Sanitary Service Company picks up your trash, the recyclables are delivered to NW Recycling in downtown Bellingham at 1419 C Street.

We are allowed to mix our plastic, glass, and aluminum because NW Recycling has the machinery to separate it all. Loads of recyclables tumble along a conveyer belt and the metal is extracted by magnets. Then, people pick out the plastics. The heavier glass drops into a separate bin. The glass is crushed, loaded into trucks, and shipped to Seattle. A facility there has machinery that optically identifies and separates glass by color. Thereupon, each separate color of glass can be melted and refashioned into new products.

Right now, NW Recycling actually has to pay to get rid of our plastic. When oil prices are low, it’s cheaper for manufacturers to buy newly made plastic ingredients, fresh from the petroleum industry. When oil prices are high, our reclaimed plastic becomes economically attractive. When there is an oil crisis, Marty says their reclaimed plastic inventory flies off the shelves, so to speak.

But this is how Marty describes the current situation: “Over the last year, it has been very difficult to ship our plastic. Mainly due to the fact that we have been shipping it to new customers. (Some to Indonesia, some domestically.) They have had to vet our material, make sure it is consistent, and make sure they have markets for it. This has been a painful process, but it has been working out. We haven’t had much trouble shipping it lately.”

Let’s Talk Trash

Like me, you may be struck by the complicated and multifaceted nature of our waste network. So far, I’ve explained recyclables and compostables. Now, let’s talk trash. My own trash is picked up by Sanitary Service Company and taken to either Recycling & Disposal Services Inc. (RDS) or to Republic Services depending on which site has room at the moment.

RDS ships garbage to the Columbia Ridge Recycling and Landfill, operated by Waste Management in Oregon. Republic Services ships their trash to a landfill in Roosevelt, Wash. Both landfills harvest methane gas from the decomposing trash and pump it back into the electrical grid. The Columbia Ridge site claims to push 12 megawatts of power back to the public every 24 hours.

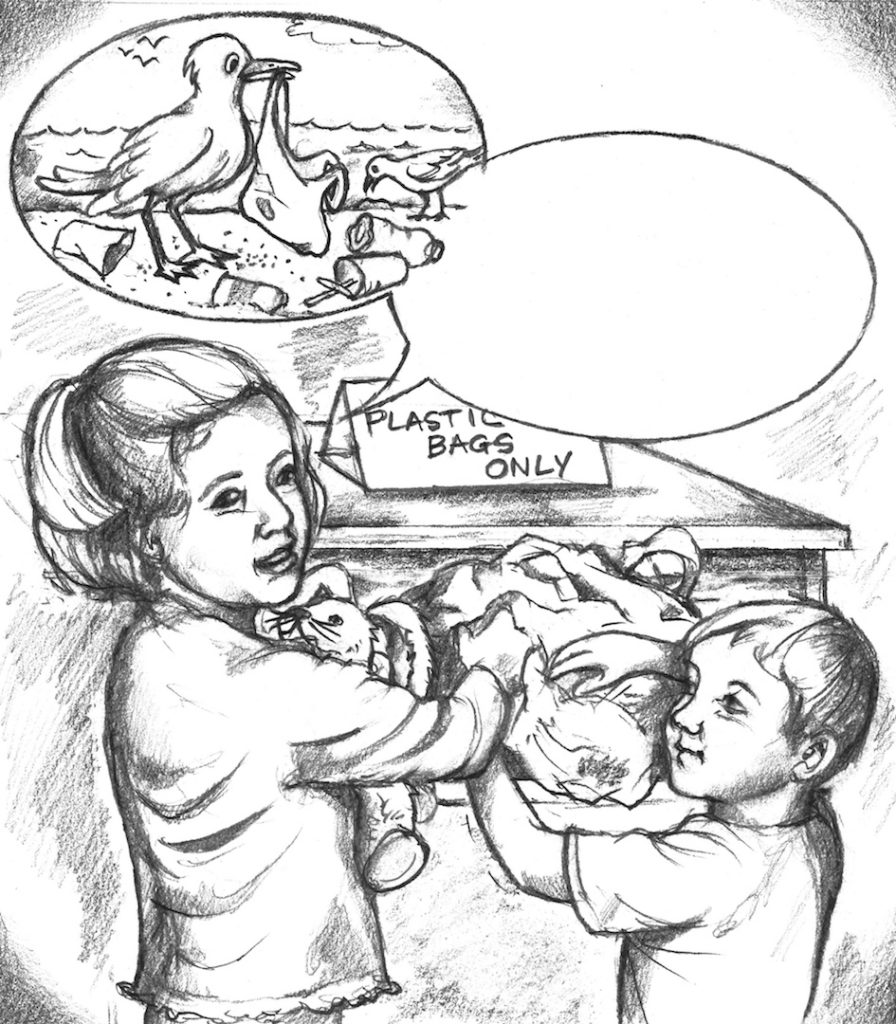

All of this research was done as a homeschool project for my children. As part of the curriculum, we watched a YouTube video showing autopsies of seabirds who had died from ingesting our plastic waste. One scientist displayed the plastic extracted from one bird and said, “This is the equivalent of a human eating three large-sized plastic pizzas.” The bird ate it. The bird fed it to its offspring. And the whole family died.

My daughter looked up at me with alarm and said, “Mom! Are the birds eating plastic that our family throws away?”

How can I answer that? How would you answer? Truth be told, any time our plastic is shipped overseas — whether it’s a new product coming to my local box store, or my old water bottles leaving toward a recycling facility in Indonesia — there is a risk that storms could knock some of the shipping containers into the sea.

For that matter, the world’s rivers regularly deliver truckloads of plastic into the ocean. According to UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), anywhere from 4.8 million to 12.7 million metric tons of plastic waste enters the oceans from land each year. To conceptualize that, take the midpoint number of 8 million metric tons and spread it over an area 34 times the size of Manhattan. You’d be ankle deep in plastic waste. (1)

Family Challenge to Reduce Waste

I could not directly answer my child. The fact is, yes, some of our plastic might end up in a seabird’s stomach. In a feeble attempt to do “our part,” my family challenged ourselves to reduce waste. This is our normal weekly metric: Nine family members send seven kitchen trash bags to landfills. To the recycler, we send one box of mixed paper along with one large trash can full of bottles, jars, aluminum, and plastic containers.

We changed our habits by taking all kitchen scraps to the garden, by bringing our old plastic bags to the Haggen’s customer service desk, and by starting a new bin of biodegradables destined for Green Earth Technology. By becoming slightly more conscientious, we reduced our landfill output from seven kitchen trash cans per week to only one. That’s right — just one!

What were the contents? Mostly nonrecyclable food packaging. I would send nothing to a landfill if my family could stop buying products with irresponsible packaging. But irresponsible packaging is everywhere and it is unavoidable for a large family on a budget. However, even if I could recycle every bit of plastic and polystyrene, is that actually better than a landfill? After all, Whatcom County can rarely find domestic recyclers. When we do, we’re the lucky ones. Most of Whatcom County’s plastic, at this moment, goes to Indonesia. What happens then?

In 2015, the journal Science published an article called “Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean.” (2) The authors listed Indonesia as one of the top five countries contributing plastic into the ocean, and blames these five as responsible for almost 50 percent of the total contribution. To be fair to Indonesia, not all of that plastic is their own — some of it is mine. I trust that Marty Kuljis believes he has found a reliable recycler in Indonesia, but news reports indicate that the country is simply overwhelmed.

According to a March 2019 article by the World Economic Forum, Indonesia recently rallied their national army to scoop plastic waste out of the river in the country’s third largest city of Bandung. The pictures on weforum.org are heartbreaking. Sergeant Sugito told the BBC, “My current enemy is not a combat enemy. What I am fighting very hard now is rubbish.” (3)

So, as I make a special trip to Haggen with two weeks of our plastic bags, I think of Sergeant Sugito. Am I really doing him and his country a favor? Maybe sending these bags to a domestic landfill is better. But out there in the Columbia Gorge, it could take anywhere from 500 to a thousand years for my plastic to decompose. I am responsible for either choice, and neither one is okay with me.

Junk Raft

A question posed by Marcus Eriksen in his book, “ Junk Raft: An Ocean Voyage and a Rising Tide of Activism to Fight Plastic Pollution,” (Beacon Press: 2017), is this: When we throw something away, where is that mysterious place called Away? He wanted to go there personally. He built a raft using Los Angeles’ waste and plastics. Then he and an associate drifted the ocean’s currents from California to Hawaii, taking 88 days to do so. Their journey mimicked the path that plastic waste takes when it leaves the Pacific Coast. The goal was to show the world how badly our oceans are being impacted by plastic.

If plastic from land finds its way into any ocean, it eventually drifts into the world’s five gyres. Think of them as very large eddies. Along the way, plastic breaks into tiny pieces the size of fish food, and also absorbs toxic pollution. Eriksen, in association with the 5 Gyres Institute, collaborated with several scientists to visit each gyre on Earth and measure the plastic found there. Experts in ocean-current modeling used their measurements to calculate an estimate of how much plastic is actually in our oceans now. The number is 5.25 trillion individual pieces constituting 269,000 metric tons.

This affects marine life and humans too. As plastic breaks down and floats around the ocean, it absorbs toxins like tiny sponges. When the plastic is ingested by fish, it moves up the food chain, carrying the absorbed toxins along with it. One study sought to measure polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in women’s breast milk. The study needed a control group with clean breast milk so they looked to the Inuit people in the Arctic. Unfortunately, due to their ocean-based diet, Inuit women carried more PCBs than women in big U.S. cities.

I’ve been led to believe that sending my plastic to the recycler is the “right” thing to do. But is it the best thing to do? My research is causing me to doubt.

Eriksen’s book provides the backstory to explain why the disposal choices for plastic are limited and pitiful. He says “go upstream” and tackle plastic at the source: Big Plastic corporations operate like Big Tobacco, spending millions to fight public perception and keep pushing plastic on us.

Remember the campaign, “Give a hoot! Don’t pollute”? It was funded by major plastic producers. They want to blame consumers for the bottles and bags strewn about the planet rather than invest effort into designing reusable and biodegradable products. Why? They have to keep making a profit, of course! So, they’ve gotten us dependent upon single-use plastics. Eriksen cites the plastic industry’s goal as “one billion tons of new plastic by 2050.” But, will the Earth’s entire marine ecosystem be completely broken by then?

Designers of plastic products and packaging need to care more about the environment than about profits. Laws can be passed to force change. Grassroots efforts and activism can create awareness. Consumers can demand more conscientious products. And, yes, I can do a better job of segregating my trash and sending each piece down the proper disposal path. I vow to compost more and I promise to pack my reusable bags to the store.

However, until Big Plastic changes its dirty ways, I cannot avoid all plastic — it’s everywhere. For now, I am grateful that Whatcom County has built a top-notch disposal network. But even the best efforts aren’t saving the planet. In time, I do believe that Big Plastic corporations will be forced out of business, and then we can all cry a few tears for them into our compost bins.

Endnotes:

1. https://www.news.ucsb.edu/2015/014985/ocean-plastic

2. Jambeck, Jenna R. et al., “Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean,” Science, pp. 768-771.

3. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/indonesia-has-a-plan-to-deal-with-its-plastic-waste-problem/

______________________________

Nichole Schmitt is a late-in-life mom and an early retiree from a technology career. Gardening and writing are her passions.