Invasive Green Crabs Found in Padilla Bay

Bob Cecile (top) and Bob Lemon inspect crabs trapped during the green crab project last summer at Post Point Lagoon in Fairhaven. No green crabs were found, although four have been trapped at Padilla Bay.

by Whatcom Watch Staff

For the past summer, crab scientists associated with the University of Washington have gathered each month at a tiny lagoon adjacent to the Post Point Wastewater Treatment Plant in Fairhaven. Their goal: to catch green crabs, an invasive species that can devastate the Dungeness crab population and cause other environmental havoc.

To date, they’ve been lucky. Not a single green crab has been found. Unfortunately, 25 miles south of Bellingham on Padilla Bay, it’s a different story. There, four green crabs have been caught, indicating that an invasion into the Salish Sea is probably well underway.

A small Hemigrapsus oregonensis, or hairy shore crab, waits in a bucket for release at the Fairhaven lagoon off Marine Park

The European green crab is smaller than the Dungeness crab but far more predatory and destructive, said Bellingham biologist Don Lemon, who volunteers with the Post Point Lagoon project. Green crabs not only eat young Dungeness and other crabs before they can flee to the protection of deeper water, but they burrow into mud and clay banks, eat native shore vegetation and destroy once pristine habitat, Lemon said.

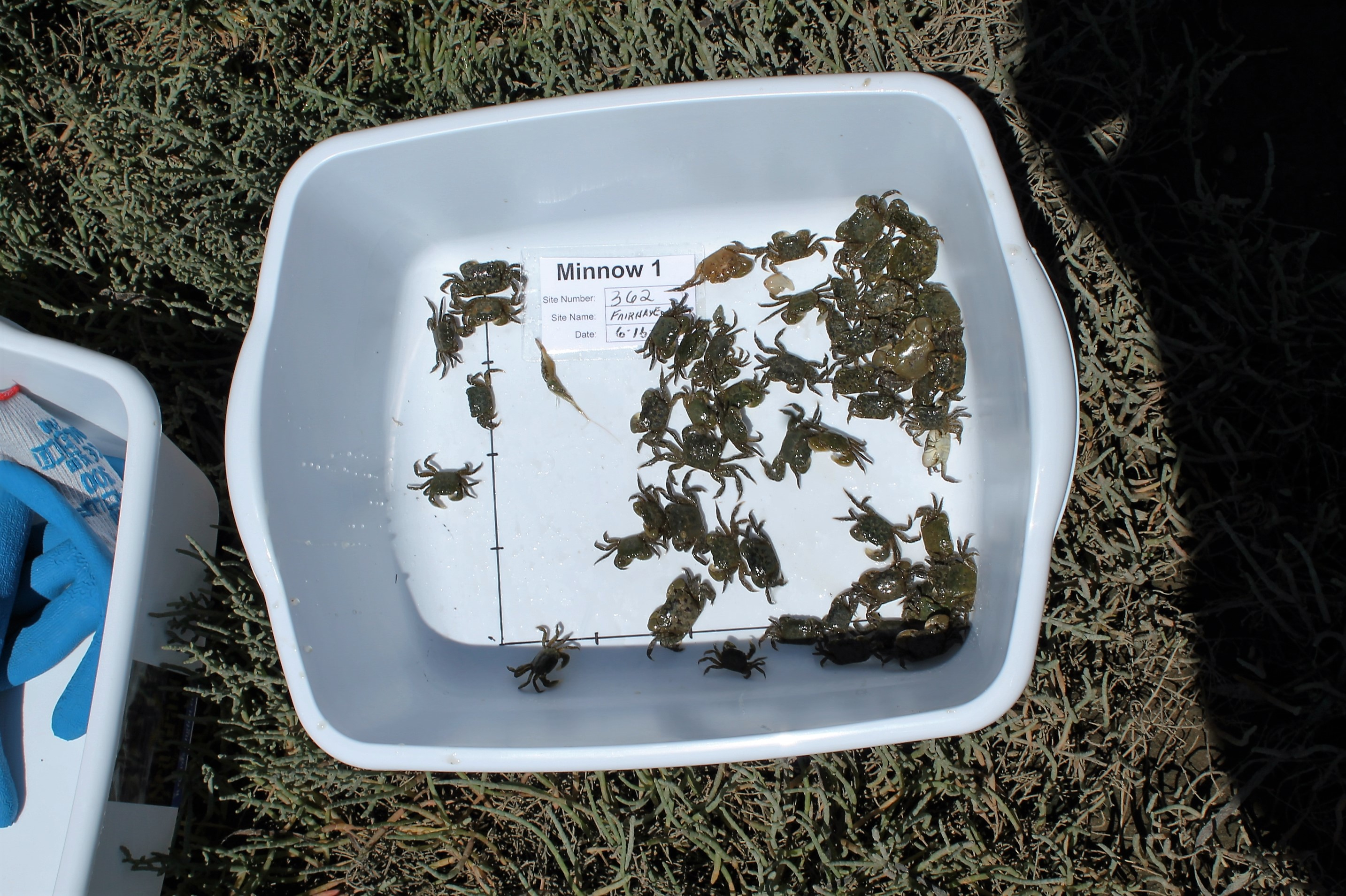

The day’s catch from one inspection minnow trap awaits at Post Point Lagoon in Fairhaven. In all, six traps are set for each count. The crabs are measured for width in millimeters, sexed and counted before being turned loose again.

The University of Washington’s Crab Team project, launched in 2015, has a mandate to monitor the green crabs. Lemon’s team has worked all summer to trap crabs in the Fairhaven lagoon, catching mostly small hairy shore crabs and purple shore crabs, which they call “oregonensis” and “nudus,” shorthand for their scientific names. They measure, sex and count the crabs, then release them. So far, it’s been really boring, Lemon said. But not much longer.

All four of the crabs caught on Padilla Bay were scattered across the bay, Lemon said. They’ll be moving north into Samish Bay, and possibly are also coming south from Drayton Harbor and Boundary Bay to the north. That places Bellingham Bay squarely in the crosshairs.

“My feeling is that this is a really critical time to get control of the situation,” Lemon said. “The larvae may be spread out every five miles or so along northern Puget Sound. All the males and females have to do is find each other, and trapping is the only known method to keep them under control.”

The crabs also may be working their way from Sooke Harbor west of Victoria out toward the San Juan Islands and Padilla Bay. One has already been trapped on the west side of San Juan Island across from Victoria.

“There’s quite a considerable population there,” Lemon said, “and it’s only a matter of time before the currents and the wind bring them here.”

“While I’m pleased that the crabs are not more abundant, it’s somewhat concerning that they are distributed so broadly,” University of Washington research scientist P. Sean McDonald said.

The UW’s research institute, Washington Sea Grant, coordinates European green crab monitoring for the state Department of Fish and Wildlife. In many places, green crabs have reduced shellfish populations and uprooted eelgrass, which is important habitat for other crabs and fish in Padilla and Bellingham bays, the experts said.

“When there are a lot of (green) crabs in a confined space eating everything they can get their claws on, they can reduce the number of clams and worms and things like that in the sediment, and that reduces the food available for other species,” McDonald said.

As a national reserve, Padilla Bay is protected for research purposes, with water quality and eelgrass beds monitored closely.

The news that a green crab had been found came just as a team of researchers and wildlife managers was wrapping up a search for green crabs in San Juan Island’s Westcott Bay, where the first confirmed green crab in the state’s inland waters was found in August, according to the Associated Press.

“We were relieved to find very little evidence of a larger population of invasive European green crabs in Westcott Bay,” said Washington Sea Grant’s Emily Grason, who heads the Bellingham project. “But finding an additional crab at a site more than 30 miles away suggests that ongoing vigilance is critical across all Puget Sound shorelines.”

Because the green crabs caught recently are roughly the same size, they are believed to be the same age, and possibly the first of their species in Padilla Bay, Grason said.

“That means there is a population that is supplying these larvae, and that means we have to keep an eye out and monitor for additional crabs to be showing up,” McDonald said.