The Nooksack River: A Treasure to Preserve

by Ron Kleinknecht

Part 3

Efforts to Reclaim the Nooksack

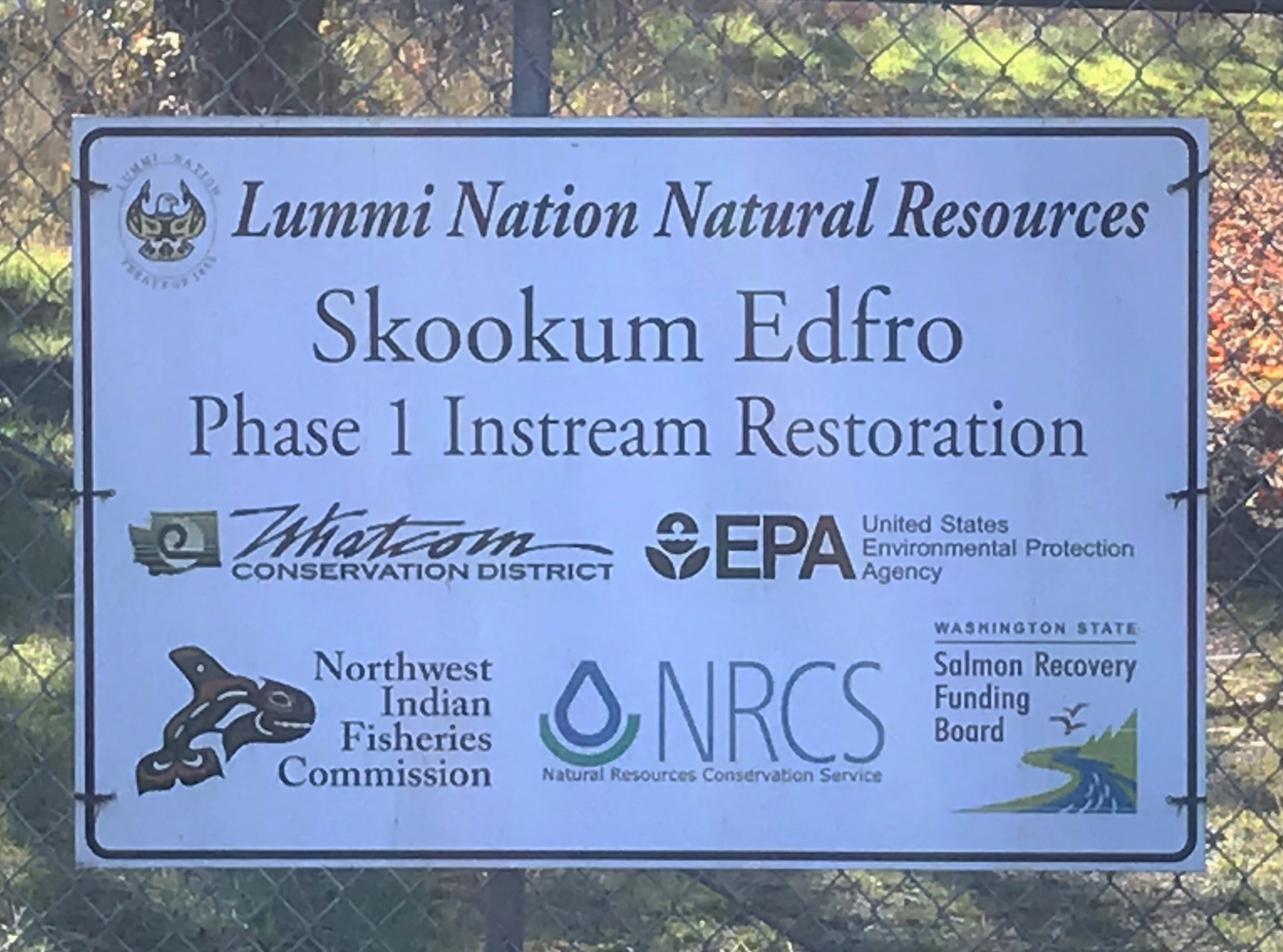

Signs like this are posted at each of the many rehab sites listing the contributing agencies — six shown here. The Skookum and Edfro are salmon spawning creeks that feed the South Fork of the Nooksack River. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

In Parts 1 and 2 of this series (1, 2), I described the Nooksack River and how its three forks joined from the glaciers and watersheds surrounding the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest and wilderness area. The river that used to be prime salmon spawning waters teemed with salmon that fed the local Indians for thousands of years. About 150 years ago, these waters were dramatically changed with the arrival of settlers from the east who logged the hillsides and plowed the prairie lands.

These typical settler activities deprived the waters of the cooling effects of the shoreline trees and degraded the water quality with flooding silt. The natural processes that sustained the waters historically became seriously disturbed. The waters and the fish suffered as a result in proportion to their proximity to the settlements. The upper reaches are less polluted than those closer to the farming and populations centers.

If it is imperative to save these salmon (and I think it is), we must first return their habitat to an approximation of that in which they evolved over many thousands of years — or at least buy them time to continue evolving to adapt to the new conditions. And since these salmon are the primary food source of the Salish Sea’s southern resident orca, the orca’s survival too is imperiled.

These salmon are also an integral part of Northwest Indian culture as expressed by the late Billy Frank Jr. of the Nisqually Tribe and leader of the Indian fishing rights and salmon restoration movements: “As the salmon disappear, so do our cultures and treaty rights. We are at a crossroads and we are running out of time.” (3)

And this is not to mention the commercial and sport fishing industries which amount to over two billion dollars a year to the state economy.

In Part 3, I describe some of the monumental efforts being put forth on behalf of these fish. Although a great deal is being done to save this fish habitat, it still begs the questions: Is it enough? Can it succeed? Following, I will illustrate some of what is being done to address the problems laid out in Part 2. By necessity, the coverage will be selective as there are too many needs, programs, and projects to cover thoroughly here.

As we begin this review of the state of the salmon in the Nooksack and the Salish Sea, and what needs to be done to preserve and restore them, it is instructive to start out with a cold hard fact of the enormity of the issue. For example, the state’s estimated cost of its recovery plans from 2010 – 2019 was $4.7 billion.

However, only about 16 percent of that amount was received by the recovery organizations and agencies charged with doing the work. (4) Where will the shortfall come from? (For further information on this issue, the reader might want to read the governor’s biennial report: “State of Salmon in Watersheds 2018” at: https://stateofsalmon.wa.gov/exec-summary/.)

Groups Working on Nooksack Project

It is surprising and heartening to see how many local, state, and national-level government and nonprofit groups are working on this river alone. There are too many groups to list list them all, so I will note some representative groups making major accomplishments and efforts focused on saving the river and the salmon.

Signs are posted at each of the many rehab sites listing the contributors. A sign at the Skookum and Edfro salmon spawning creek area indicates five agencies, including federal, state and Northwest treaty Indians, are working on the South Fork of the Nooksack.

Following are some of the numerous agencies and organizations involved in the effors on the Nooksack River. I will refer to many of these along the way.

Tribes

• Treaty Tribes of Western Washington (3):

• Nooksack Indian Tribe — Natural Resources Department

• Lummi Indian Tribe — Natural Resources Department

• Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

Federal Agencies:

• Environmental Protection Agency

• Department of Agriculture

• National Resources Conservation Service

• National Forest Service

• National Marine Fisheries Service

• Department of Interior

• AmeriCorps

• NOAA

State Agencies:

• Department of Transportation

• Department of Ecology

• Washington Conservation Corps

• Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

• Salmon Recovery Funding Board

• Water Resources Inventory Area (WRIA 1)

Local Environmental Educational Programs:

• Western Washington University, Huxley College of the Environment

• Whatcom Community College environmental studies

• Bellingham Tech College: fisheries studies

• Northwest Indian College

Whatcom County and Departments:

• Whatcom Watersheds Information Network (WWIN)

• Whatcom Conservation District

• Whatcom Co. Planning and Development Services

• Whatcom County Parks and Recreation

Cities (several agencies)

• Bellingham Dept. of Natural Resources and Environment

• Bellingham Public Works Services

Non-Governmental Organizations:

• Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association

• Whatcom Land Trust

• RE Sources for Sustainable Communities

• American Rivers/ Nooksack Wild and Scenic

• Trout Unlimited, Northwest Chapter

That is a lot of groups working on and in this one river and there are more groups and more rivers. Also encouraging is the extent to which these various groups join forces to tackle given issues. Although the groups have somewhat different overall missions, one thing they all have in common is the desire to restore and preserve the river habitat and watershed such that it best sustains salmon from hatching to return and spawning.

Stream Restoration

Stream restoration is essential to providing salmon with the environment they need to spawn and for their young to mature as they grow and prepare to go to sea. The fish need room to swim, river bottoms suitable for making redds, pools of slow water for the hatchlings/fry to mature, cool and clean water with adequate nutritious food (macroinvertebrates) for them to grow during their first year. It will take several stream restoration components to mitigate the problems with the Nooksack, two of which will be mentioned here.

Habitat Corridor Restoration

One of the largest undertakings on the Nooksack is restoration of the water quality and the riparian (shore and related wetlands) corridors of the river itself, along with the tributary creeks where salmon spawn and spend their first year.

Riparian corridors along the lower portions of the Nooksack and its tributaries were largely destroyed as settlers moved in and cleared the flatland forests for farms along the rivers and streams. Further, hillsides were denuded for the plentiful and prime Douglas fir, Western red cedar and other trees destined for building materials.

After people uprooted and stripped the trees and native undergrowth, our prolific rains washed the unsecured soils into the rivers, which often then overflowed. This flooding washed out the previous natural barriers that provided pools and slow water for spawning areas. In addition, the bared river banks provided no protection from summer sun, which raised water temperatures to unsafe levels for the fish. This overheating is expected to increase with imminent climate change.

These river banks and adjoining riparian areas are now the prime targets for stream restoration. Land-clearing and logging regulations have slowed this degradation, but much remains to be rebuilt. Local nonprofit organizations along with the Lummi and Nooksack tribes have taken up the task with assistance from state and federal agencies to restore these trees and undergrowth along the streams — largely with volunteer labor from our community.

Information kiosks, snack tent and science demonstrations at a tree planting work site. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

On a chilly March Saturday, my granddaughter and I joined a volunteer work party at Kendall Creek with the task of planting new trees and shrubs along a wetland fed by the creek. Approximately 40 volunteers of all ages and representing several different cooperating agencies joined in and planted over 1,300 willow, spirea and red-osier dogwood shrubs, and removed 540 pounds of invasive Himalayan blackberry vines. These new plantings will stabilize the soil, hold water, and provide shade for cooling the creek.

Future work parties will be needed to finish this job of planting as many as 10,000 willows on this site alone. At other sites, larger native trees are planted, such as Douglas fir and Western red cedar. Four of the entities involved in this particular project were the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association (NSEA), the Whatcom Land Trust, Whatcom Conservation District and Trout Unlimited. The project also included Kendall Elementary School, as the creek is in their backyard, along with a number of student interns from WWU.

Joint agency work parties such as this one occur most weekends throughout the year. Although they do make headway at each project, it will take years of this type of action to fully restore the riparian corridors along the Nooksack watershed. These work parties are typically held on Saturdays and are open to all ages. They last only three hours, from 9:00 a.m. to noon and always provide donated coffee and snacks.

While this replanting is going well and there have been hundreds of volunteers of all ages willing to come out on cold and foggy mornings, the task is enormous. But we persist. Many more planting parties by these and other groups are scheduled throughout the Nooksack watershed.

Restoration Activity Statistics for 2018

Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association

1,142 Volunteers

4,219 Hours Volunteered

3,688 Trees/Shrubs Planted

Whatcom Land Trust

858 Volunteers

6,006 Hours Volunteered

2,500 Trees/Shrubs Planted

Whatcom Conservation District

24,860 Trees/Shrubs Planted

If you see the little blue plastic tubes along streams throughout the county, you will know that one of these groups has been there. These tubes protect the young seedlings by keeping the rodents and other critters from gnawing on the new plants. For larger plants and trees, wire cages are constructed to keep deer and elk from grazing on them.

Much of the native vegetation planted by these groups is grown at NSEA’s nursery.

Much of the native vegetation planted by these groups is grown at NSEA’s nursery. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

Fish Barrier Removal

Early roads and wagon trails were built throughout the county to allow settlers to travel and to transport crops and lumber to market. These roads crossed and forded the many streams that ran into the Nooksack. In 1917, when cars became more popular, the state started to build roads and highways, and when they crossed streams, round pipe culverts were installed to allow stream flow.

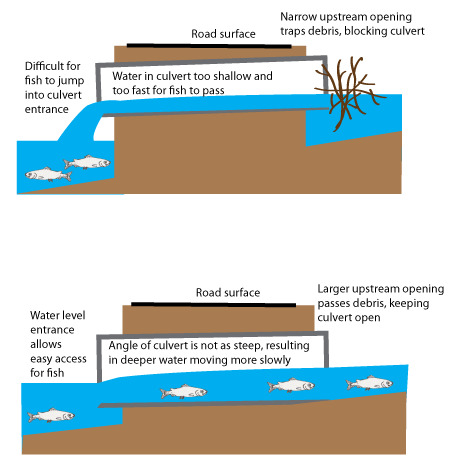

However, these culverts under the roadways were, and often remain, barriers to fish attempting to reach their spawning grounds. (5) Culverts often narrow the stream, which increases water velocity and turbidity, and, in many cases, totally block passage with built-up debris. Such blockages, of course, reduce the number of eggs that can be deposited, fish hatched, and, ultimately, the number of salmon returning.

By the 1990s, scientists clearly recognized that these barriers affected salmon breeding and therefore reduced the numbers available for sport fishing and for commercial harvest. Although culvert removal has been an ongoing project for the state for some 25 years, it was expensive and was moving forward too slowly to effect significant increases in salmon productivity.

In 2001, concerned with the pace of culvert removal and the declining salmon stocks, 21 treaty tribes of Western Washington took the state to court. This lawsuit began a 17-year-long court battle alleging that the culverts’ presence violated their treaty rights to fish in their usual and accustomed places, and that the culverts prevented them from to be able to earn a “moderate living” from fishing as per the treaty and its interpretation in the Boldt Decision. (6)

This 1974 “Boldt Decision” interpreted the meaning of several 1850s treaties between the government and the tribes that stated treaty Indians retained “the right to fish in common with white fishers,” and interpreted as the right to catch one half of the fish. The result of this 2001 lawsuit was that, in 2007, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found in favor of the tribes, and, in 2013, the court issued an injunction that required state agencies to correct fish passage barriers under state roads.

The state then appealed this decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court vote resulted in a 4-to-4 tie in June 2018. With a tied vote, the case was sent back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit that had already ruled in favor of the tribes. (7)

Finally, this ruling meant that the state had to pay for the removal of about 1,000 culvert barriers statewide at an estimated cost of $3.7 billion. The court also ruled that 90 percent of the offending culverts were to be removed by 2030 at a cost of about $2.4 billion. The Department of Transportation, which is responsible for road replacement and repair, is actively pursuing this mandate (8), while the Washington state Legislature is currently grappling with how to find the money to comply with this important but expensive decision.

An example of culvert removal and creek restoration of High Creek that runs under State Highway 542, (the Mt. Baker Highway). Plantings are in process. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

There are several recently completed under-road habitat restoration projects along State Route 542 (the Mt. Baker Highway), such as one crossing High Creek, which runs into Kendall Creek before entering the Nooksack. That habitat improvement project includes rebuilding the creek bed and sloped banks planted with native shrubs that will help retain the soil and cool the water for salmon.

These examples illustrate some of the robust stream rehabilitation work that is currently underway restoring the Nooksack watershed, the river and its tributary creeks to a state approximating that in which the salmon evolved and in which they can continue to survive and be productive. Fortunately for us and the fish, much more is being planned and completed. (9, 10)

In the final part of this series, I will address issues associated with Whatcom County agriculture that have contributed to the decline of the river along with some of the efforts, technology and goodwill that are now being expended to right those wrongs. Finally, I will provide an assessment of the current state of habitat restoration and prospects for salmon in the Nooksack.

Next Month: Part 4

Righting Past Wrongs on the Nooksack

References

1. Whatcom Watch, March 2019

3. https://nwtreatytribes.org/habitatstrategy/ (Billy Frank)

4. https://stateofsalmon.wa.gov/exec-summary/

5. https://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/fish_passage/solutions/Culverts.html

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_v._Washington

8. https://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/do/EB4EFB8E-86632129A3306A71A10F0D04.pdf

9. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/Projects/FishPassage/CourtInjunction.htm

10. http://salmonwria1.org/resources/documents

_____________________________________

Ron Kleinknecht is professor emeritus of psychology and dean emeritus of Western Washington University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He’s a lifelong nature and conservation enthusiast who writes about the Pacific Northwest and is a volunteer land steward for the Whatcom Land Trust.