What WTA, the City of Bellingham and Major Employers Could Learn from Kingston Transit

by Preston L. Schiller

How Kingston Transit Was Reformed

Part 2

Brief Review of Part 1

Part 1 of this three-part series on Whatcom Transportation Authority’s (WTA) bus system described and documented its trend of stagnation and decline in ridership after a period of dramatic ridership growth over a decade ago. It also discussed the importance of transit for urban and rural areas, and why good transit is a key ingredient for managing urban growth and reducing transportation-related pollution.

Part 1 noted that several factors, from the introduction of a few limited GO Line corridors where buses were relatively frequent, to the passage of a universal transit pass by WWU students, that promoted its rapid ridership growth between 2004 and 2009. It hinted briefly at several reasons for WTA’s recent decline, including its over-dependence on the sales tax for support and its adherence to a pulsing hub and spoke route system.

And, Part 1 offered a comparison of WTA’s trend with that of the transit system of Kingston, Ontario, (KT) which, starting from a weaker position than WTA’s, initiated a reform effort that has accomplished great ridership growth in the past decade.

The current article examines the ingredients of Kingston Transit’s “secret sauce,” and discusses the shortcomings of WTA’s pulsing hub-and-spoke system as well as its form of governance. It offers suggestions for WTA in these regards. It also touches upon a few of the lessons that WTA should have learned from its exposure to the highly successful innovations of GO Boulder (CO) it was exposed to several years ago. In a subsequent Part 3, I will explore what WTA, the city of Bellingham, Western Washington University (WWU), Whatcom County, major employers such as PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center and citizens can do to improve transit in their respective and collective domains.

This series is written with the intent of offering a constructive critique of aspects of WTA and with the hope that several of the candidates for local and county offices in the upcoming election will begin to pay more and better attention to this vital issue.

Kingston Transit’s Not-So-Secret Sauce

There is no “silver bullet” for transforming a transit system and rapidly increasing its ridership. Many factors combined led to the transformation of Kingston Transit between 2009 and 2019. A few of the most important are presented here as a prelude to a discussion of what WTA and other major actors, such as local governments and large employers, can do to grow ridership. (1)

KT changes were initiated by discussions between engaged citizens, City Councillors, and the city’s city administrative officer (CAO) before the problem of agency stasis and ridership stagnation reached crisis proportions. In 2008, the city began a series of policy-led changes encompassing new management, including administrative, marketing, and planning expertise, as well as consultants whose expertise fit well with the agency’s needs.

Some of the engaged citizens were affiliated with Queen’s University, enabling the agency to tap into their resources and talents. Several students have done research papers addressing issues relevant to the agency, while others have been offered part-time employment.

More recently, policymakers and engaged citizens, including the advocacy group Kingston Coalition for Active Transportation (KCAT), have pushed transportation planning toward the goal of a 15 percent mode share for transit — currently around 9 percent, and a 20 percent mode share for walking and cycling — currently around 12 percent, by 2034.

In addition to introducing four express routes between 2013 and 2018, KT introduced a “Train Station Circuit” (Route18), connecting the downtown transfer point, Queen’s University, St. Lawrence College, and the neighborhoods along the way with VIA Rail Canada and Coach Canada-Megabus stations. With no restrictions of having to meet a pulse or timed transfer with other routes, buses are able to idle for a few minutes at either station in order to meet a train or bus that is running a few minutes late. This has proven to be a very popular option for students and other residents.

Increase in Pass Holders

A few other routes were eliminated or modified due to low ridership or redundancy with the express routes. Rider amenities have improved considerably over the past decade as well. The number of shelters has increased by 80 percent, from 130 in 2009 to 234 in 2018. The ratio of bus shelters to bus stops has increased from 15 percent to approximately 29 percent in the same time frame.

An extensive pass program with a variety of options tailored to the needs of distinct populations has been developed since 2009 (City of Kingston Transit Fares). In some cases, specific service planning considerations were taken into account, as when the new frequent express route (501-502) serving Kingston General Hospital (KGH) was timed to arrive a little before and a little after shift changes.

There are now over 800 employees of KGH and its downtown clinics at Hotel Dieu Hospital and over 400 employees at Queen’s University enrolled in the Transpass program. The “Employer Transpass” is now available through approximately 100 employers. In cases where a major employer was not willing to take on the responsibility of organizing an employee pass program, KT has identified an interested employee volunteer for this purpose.

Where a number of smaller employers are clustered in one locale, such as those of the Downtown Business Improvement Association (DBIA) or the Cataraqui Centre (a mall with a transit sub-center), employers are treated as one group so that they can receive the highest cost reduction possible for a monthly unlimited pass. KT also introduced a “loyalty program,” PassPerks, which provides pass holders opportunities to save at a growing list of local stores and services. By making its services and amenities of greater value to commuters KT has been able to increase the number of pass holders considerably.

Better outreach to student populations has often led to rapid increases in ridership. Many Queen’s University students were unaware that for many years their student association had been disbursing a portion of student fees to Kingston Transit in exchange for all students’ ID cards serving as transit passes. Once this became more widely publicized, student ridership climbed quickly. Students at St. Lawrence College, located along an express route, are also increasingly drawn to a student pass program.

In 2012, a pilot program providing free transit passes to beginning grade 9 students was initiated. Supported with a small subsidy from the school district to KT, it proved to be a tremendous success. After careful evaluation, the program was expanded to all high school students. The pilot year effort led to 28,000 transit trips, with the latest year’s data reporting 600,000. As a result of its success and popularity, local school districts have increased their financial contributions considerably.

A special program invites groups of art students to decorate bus shelters after learning more about the surrounding neighborhood and its history. A specially decorated and outfitted bus is deployed to schools in order to teach students ridership and rider etiquette. In 2017, Kingston Transit, with approval from the council, initiated a policy that all youth under the age of 14 could ride for free and did not need a pass or ID. The policy was intended to attract families with children to travel by transit, but it does not require youths to be accompanied by adults. It appears to be attracting families with children as well as youths traveling solo.

The city of Kingston controls a great deal of downtown parking, in lots and structures, as well as on-street parking throughout the city. In dense areas lacking in sufficient off-street parking, car owners can purchase an on-street parking permit. The city has raised monthly parking pass and permit fees to exceed the cost of a transit pass, thus encouraging daily car commuters, or even residents in areas subject to on-street controls, to consider transit. Attendees at major events at the downtown event centre, including professional hockey games, are encouraged to ride the bus rather than drive, thanks to a low fare of one dollar, a bargain compared to parking fees.

The creation of segments of bus bypass lanes from existing underused and very long turning lanes, sometimes only serving a commercial area, is being studied, as is expanding transit signal priority and queue jumps at some crowded interchanges. Such measures will speed buses along their route and save money for the service. Some efficiency measures already introduced are expected to save KT a considerable sum. Between 2017 – 2021, an estimated $1 million reduction in capital expenditure has been identified as a result of reductions in fleet requirements gained through operational efficiencies created by the real-time GPS tracking system, transit signal priority, and the installation of a new farebox system that reduces passenger boarding time.

WTA Governance Issues

A contributing factor to WTA’s problems is the way in which it is governed and administered. No doubt the Legislature and Governor Dan Evans meant well when they established legislation enabling the formation of Public Transportation Benefit Areas (PTBAs) in 1975 (Revised Code of Washington; RCW Chapter 36.57A). The PTBA is the framework within which the large majority of Washington transit systems operate. A comprehensive discussion of the history, benefits and drawbacks of the PTBA framework is beyond the scope of this article, but a few of its problematic aspects as embodied in WTA’s governance deserve, at least, cursory examination.

RCW 36.57A specifies that “PTBAs are governed by a board of up to nine elected officials selected by the legislative bodies of the county and the component cities.” However, there is little-to-no guidance about how a board should be constituted or whether all board members need to be elected officials. Nor does 36.57A rule out board membership by school board, fire district or public hospital representatives.

WTA’s board consists of nine elected officials and one non-voting union representative. At present, the nine elected officials include Bellingham’s mayor and two councilmembers, Lynden’s mayor, Ferndale is represented by two councilmembers, Blaine/Birch Bay is represented by a Blaine councilmember, Everson/Nooksack/Sumas by Nooksack’s mayor, and Whatcom County by its executive and one councilmember.

There are several problems inherent in such forms of federated (as opposed to directly elected) governance. Firstly, it is not clear that it meets the criterion for “one person — one vote” representation; Bellingham is probably underrepresented on WTA’s board, while the small cities, hamlets and rural areas of Whatcom County are probably overrepresented.

Secondly, since no one is directly elected to the WTA board, it is likely that interest in transit is very uneven across its members; for some it is just another chore that takes them away from other governmental tasks vying for attention; for others it is an opportunity to flex some muscle about wanting more services for their constituents — even if their constituents are not interested in or able to use such.

Given the past formal and informal opposition of many outside of Bellingham, especially Lynden’s elected officials, to a WTA sales tax increase on the ballot a few years ago, one has to wonder whether they understand transit or want it improved. One has to wonder whether board members are sincerely interested, ever ride the bus, go to transit conferences and workshops, or direct their jurisdictional staff to develop some expertise in transit so as to interact more productively with WTA staff and planning processes.

While WTA staff are reluctant to estimate how much of its ridership or revenue is based on Bellingham, it is clear from examining the ridership for certain routes and destinations as well as pass revenues that the great majority of ridership and revenue is generated within Bellingham, especially around Western Washington University, downtown, and, to a lesser extent, around Whatcom Community College. Why are they not represented on WTA’s board?

One might also wonder about the relationship of WTA’s governance structure and board politics to some questionable investments in or locations of park and ride lots in Ferndale and Lynden. The Ferndale lot is located on the east side of I-5, away from its downtown and very difficult to access by foot or bicycle. One has to wonder about the extent to which these are overbuilt and underused, especially since Lynden’s Route 26 ridership has been declining. In general, park and ride, as a transit investment, is open to question when compared with other options. (2)

WTA’s overreliance on a portion of the sales tax for the largest portion of its funding is problematic for several reasons: County conservative-led defeat of a levy increase, as occurred in 2010, can lead to cutting of service; sales tax revenues can fluctuate widely depending on the state of the U.S. and Canadian economies; in times of recession, or when the Canadian dollar is weak relative to the U.S. dollar, sales tax revenues will fall. Some transit agencies try to have a more varied portfolio of revenue sources in order to avoid the “feast or famine” problem.

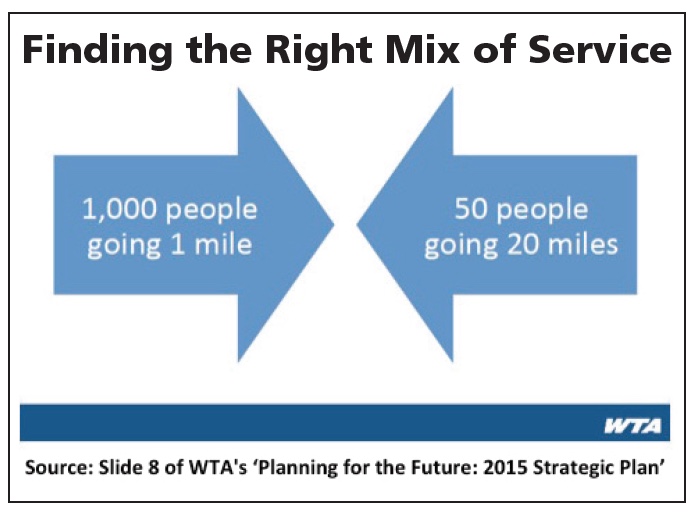

The assumption by WTA that “carrying 50 persons 20 miles each is just as good as carrying 1,000 persons one mile each” is highly questionable. Transit actually has more overall benefit when it carries more people relatively short distances.

Kingston Transit’s Growth

Early on in its reform, Kingston Transit made the decision to not abandon the downtown hub and spoke (also known as “radial”) and sub-center pulse system for those routes tied to it for now, but to go around its limitations with the new routes. Currently, the new express routes have attained about half of the peak period ridership.

As express route ridership expands and some other routes are made more frequent, it is possible that the pulsing system may only be necessary for infrequent routes — at least during weekday hours; frequent service obviates the need for pulsing and timed transfers, as the Kingston and Boulder experiences demonstrate; riders are willing to walk a little farther to stops that are a little more widely spaced in order to use a bus that is faster and more frequent than a pulsed route service.

Transit agencies should not fear introducing new and innovative routes or eliminating others, especially if done incrementally with sufficient time to involve the public and make adjustments when needed. Often there can be surprising, even dramatic, successes — as in the case of the KT express routes and its train and coach station circuit route.

The GO Boulder (CO) planning unit has been a leader in sustainable transportation for decades. Dissatisfied with the standard lackluster routes furnished by Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD), Boulder began designing its own complementary Community Transit Network (CTN) with maximum citizen participation in the early 1990s. Over the course of a decade, 10 new fast and frequent routes spanning the city were introduced. All but one have been great successes. Some are direct routes that do not pass through the downtown transit center or pulse with other routes; service frequency obviates the need for pulsing.

Accompanying Boulder’s Community Transit Network were several pass programs targeted at students, employers and employees, even neighborhoods. Having a transit pass became a badge of civic pride. At present, approximately 80 percent of residents have passes and Boulder is considering ways of establishing a universal “Boulder Pass” encompassing all residents. (3)

The Problems With Pulsing

The idea of a bus pulsing or timed-transfer system was developed by the Edmonton, Alberta, transit planner John Bakker — a well-trained engineer and post WWII Dutch emigré who brought an understanding of good transit along. Bakker also brought the notion of light rail transit (LRT), a hybrid of streetcar and metro rail approaches, via Edmonton — the first North American LRT system. (4) But Bakker and his colleagues did note that congestion and other sources of delay could hamper the efficacy of the timed-transfer.

Bus pulsing dictates the amount of time that a bus has to cover its route. If buses have to regularly pulse with numerous other buses on a schedule of once an hour, or twice an hour, or four times an hour, their routes can only be so long — either in distance or time. A bus system can only accomplish this by assuring that all the buses involved can maintain a certain average speed, or by building extra time into the schedules of each, or allowing faster buses more layover time at the pulsing point (such as the downtown or Cordata transfer centers) until the slower buses arrive.

A finely tuned pulsing system, where all the parts are efficiently synchronized, can provide an efficacious way of deploying buses. When traffic congestion, frequent stops, and slow passenger boardings delay even one part of the system, all parts of the system are slowed. It is possible that WTA has made its pulsing system sort of work by building extra time into routes or layovers. Time is money in a significant way in bus transit as its most expensive operating cost is drivers’ wages. More operating costs translate, in WTA’s case, to less service overall. Less service, where most productive, as in corridors of greater population and travel density, translates into less ridership.

Although the goals of the pulsing hub-and-spoke system include bus fleet optimization and easier access to more destinations, it accomplishes these through forcing a higher rate of passenger transfers than more direct (and frequent) systems do. Experts whom I have consulted inform me that a well-functioning bus-only system probably should have a transfer rate in the range of 20 to 25 percent or more; WTA’s is slightly less than 11 per cent. And, unless transfers are very quick and easy to make, riders tend to resent moving from one bus to another. Riders prefer simple schedules that adhere to “clockface” — the bus can be expected at certain times and equal intervals throughout the day and evening.

In recent years, WTA has tried to move a little away from a pulsing system for all of its routes all of the time — as its consultant noted in a paper responding to requests from transportation commission members involved in the 2015 strategic planning effort, to reconsider its over-dependence on pulsing. (5) A more frequent route, such as the 232, does not mesh exactly with less frequent routes. Some routes serving special purposes, such as shuttling between WWU and nearby destinations such as downtown or the Lincoln Creek park-and-ride lot, may not mesh that well with many other routes as well.

WTA has also attempted to optimize fleet efficiency in its hubs and spokes by interlining bus routes with each other; a bus that enters the downtown transit center as one route may be transformed into a different route rather than simply turning around and remaining the same route in its opposite direction. But this identity change does not occur for all routes for all runs; it may be adding to the confusion of a system that already might be characterized as having too many routes, too many schedule shifts, and too many pages in its schedule book.

WTA, and it is not alone in the transit world in this regard, is forcing its bus deployment and scheduling model to fit into the procrustean bed of pulsing and fleet optimization. It is allowing the tail of pulsing to wag the dog of more rider-friendly transit service and facilities planning. Generally, these strategies do not lead to a more transparent, user-friendly system. (6)

WTA Needs Imaginative Thinking

There are several competent and well-trained staff at WTA who are open to new ways of imagining transit improvements. There are staff recently new to WTA who bring valuable experience from previous postings. An example of WTA’s creativity and competence can be found in the ways in which it has been branding the GO routes and many of its bus shelters.

But one senses that the overall thrust of the WTA board and its highest management is to maintain “business as usual” and not get out of the box in which it feels comfortable. Business as usual might be alright when all is functioning well and a system is thriving. But, when the trend line, as in WTA’s ridership for the past several years, is going in the wrong direction, it is time for a new approach.

As discussed in Part 1 of this series, (7) WTA’s 2004 strategic planning effort, although incomplete, still led to several service planning modifications and marketing efforts that resulted in significant ridership gains.

This was not the case with its 2015 strategic planning effort. (8) That effort was mostly oriented to a review of relatively minor changes to its business-as-usual approach. Several participants in the 2015 effort were representatives of Bellingham’s Transportation Commission. When they raised questions about considering alternatives to the pulse system, such as greater frequency and less pulsing, they were assured, in effect, by WTA staff and its consultant, that “everything was fine with the way things were, thank you, and let’s move on to discussing minor tweaks to routes.”

An example of the poor thought that was inherent in the 2015 effort can be found in WTA’s “Planning for the Future: 2015 Strategic Plan” presentation of its approach, shared early on with participants and made available to the public through its website. In discussing how it would balance the needs of urban riders with those of outlying small town and rural riders, it presented a diagram (see page 8: Finding the right mix of service) suggesting that “1,000 people going 1 mile” was equivalent to “50 people going 20 miles.”

WTA’s arithmetic is correct: 1,000 multiplied by one equals 50 multiplied by 20. But WTA’s thinking, in terms of transit planning, is muddled and stuck in a false equivalency. Transit works best and is most efficient when it is carrying large numbers of persons over relatively short distances. As a vital public service, it may need to devote some small portion of its resources to transporting smaller numbers of persons over relatively longer distances — but this should not be its major thrust.

A well-paid bus driver transporting 1,000 riders averaging a one-mile trip each is generating much greater revenue and benefit than a bus driver transporting 50 riders for a 20 mile trip — especially when the fare collected for a one-mile trip is the same as the fare collected for a 20-mile trip. And, as previously noted, the public subsidy per short urban ride is much less than the public subsidy for a longer rural trip.

WTA needs to be rescued from such flawed thinking and from the procrustean bed it has made for itself in regard to its service planning orientation. This will be explored in the next issue’s Part 3, as well as examining what WTA, the city of Bellingham, Western Washington University (WWU), Whatcom County, school districts, major employers and citizens can do to improve transit in their respective and collective domains.

Part 3 (In a future issue)

Improve transit at St. Joseph PeaceHealth Medical Center.

Endnotes

1. A more complete discussion of KT’s transformation can be found in “How Kingston doubled its transit ridership within 10 years,” Plan Canada, the official magazine of the Canadian Institute of Planners, Fall 2019. Parts of this section are influenced by this article.

2. See the discussion of park and ride in Schiller and Kenworthy, “An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation,” 2nd Edition, Revised. Routledge, 2017

3. Schiller & Kenworthy, Chapter 9 and personal communications with city of Boulder personnel.

4. Some years ago I was able to coax Bakker, also a staunch advocate for improving inter-city rail, out of his central B.C. retirement to meet with a group of mostly local government officials in our region about how to preserve the second daily Amtrak Cascades service, then threatened by funding cuts, but, unfortunately, he did not have time to give a presentation about the pros and cons of a pulsing timed-transfer system.

5. Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates (undated) “Hub and Spoke the Best Design for WTA?” Working Draft prepared for the Whatcom Transportation Authority (2015?)

6. More on user-friendly transit in Part 3.

7. As well in several of my previous articles from that time in Whatcom Watch’s archive.

8. I monitored this exercise from the sidelines, but I was in close communication with several members of Bellingham’s Transportation Commission who were formal and critical participants in it. I am indebted to their files and memories for assistance in furnishing some key information for this article.

___________________________________

Preston L. Schiller is the principal co-author of “An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation, 2nd ed. revised,” 2017. In the early 2000s he led an exchange between Bellingham and Boulder (CO) around transportation and transit issues that helped foster creating Bellingham’s Transportation Commission. He teaches in the University of Washington’s Civil and Environmental Engineering’s Sustainable Transportation Master’s program and has taught transportation planning at WWU’s Huxley College and Queen’s University (Kingston, ON). He led the preliminary research and planning that created the express bus routes connecting Bellingham, Mount Vernon and Everett. His prior articles about WTA can be found by an author search at whatcomwatch.org; recent as well as previous issues Jan. 2002 to Sept. 2015.